Key points:

- United Methodist legal experts offer an update on the impact of President Trump’s immigration policies and a guide of rights when interacting with federal immigration enforcement agents.

- But after the deaths of Renee Good and Alex Pretti, United Methodist legal experts acknowledge that asserting U.S. constitutional rights can come at great risk.

- Nevertheless, they also say that peacefully documenting immigration enforcement actions in public spaces is key to accountability long-term.

United Methodists have good reason to stand up for basic rights — especially when those rights are being ignored or violated.

The United Methodist Church’s Social Principles declare that all individuals — no matter their circumstances — deserve basic human rights and freedoms. These include the right to life, liberty, security as well as equal treatment before the law and freedom from unlawful detention.

“These rights are grounded in God’s gracious act in creation (Gen. 1:27), and they are revealed fully in Jesus’s incarnation of divine love,” say the General Conference-approved social teachings.

“As a church, we will work to protect these rights and freedoms within the church and to reform the structures of society to ensure that every human being can thrive.”

But for many church leaders, President Trump’s second term is putting these principles to the test.

Join the public witness

Several United Methodist agencies — Church and Society, Religion and Race and the United Methodist Committee on Relief — are participating in an ecumenical and interfaith worship service and march on Feb. 25 in Washington, D.C., calling for the humane treatment of immigrants. This is an opportunity to show solidarity for immigrants and call upon Christians everywhere to live out Christ’s call in Matthew 25 to “welcome the stranger.”

The Immigration Law and Justice Network — a United Methodist ministry with legal clinics across the U.S. — has been keeping up with the impact of Trump’s immigration policies and what they mean for basic human rights. The ministry released an update Jan. 26 in English and Spanish that also gives guidance for interactions with federal officials — Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Border Patrol.

It should be noted that simply being in the U.S. illegally is a civil offense, not a criminal one.

The guide also notes that the Constitution’s Fourth Amendment protections against “unreasonable searches and seizures” still apply to everyone in the U.S. regardless of their immigration status.

However, the guide also acknowledges that asserting U.S. constitutional protections to Immigration and Customs Enforcement or Border Patrol now can carry a heavy price.

“It is important to do a personal risk assessment grounded in knowing your constitutional rights but also knowing the trends of immigration enforcement in your area and making a determination for yourself on what to do next,” said Melissa Bowe, an attorney and co-executive director of the Immigration Law and Justice Network.

“The stakes are high, and insisting on our rights comes with more risk and could intensify one’s interaction with these ICE or Border Patrol agents.”

Federal immigration enforcement agents have used increasingly aggressive tactics including entering homes without judicial warrants, breaking car windows to pull people from their vehicles, separating children from their families and fatally shooting two observers — Renee Good and Alex Pretti.

Since Trump’s second term began a year ago, immigration agents have killed four people in their operations and another 32 people have died in detention centers — a 20-year high.

The New York Times reported that for the past month, agents have seized more than 100 refugees in Minnesota and sent them to a detention center in Texas to be revetted. Those released have needed to pay their own way back. The refugees all have no criminal record and are here legally in the U.S.

The agents’ tactics have received rebukes in court, sparked public outcry and now face scrutiny in Congress.

Amid this intensifying public attention, Bowe said it is important for those who feel safe enough to insist on their rights to record and document immigration enforcements’ actions.

“This is one of the only ways we can try to hold immigration enforcement accountable to the general public and accountable long term,” she said.

Global response to Minnesota

Federal immigration officials’ crackdown in Minnesota has drawn condemnation around the globe.

Here is an overview of some statements:

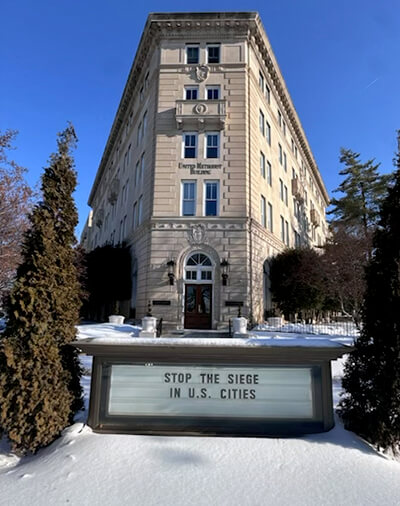

The United Methodist Council of Bishops condemned the violence in Minnesota. “The violence being perpetrated on our streets, the loss of safety, and the inhumane treatment of God’s children, are hurting us all,” the bishops said.

The World Council of Churches, of which The United Methodist Church is a founding member, called for an independent investigation into the killings of Renee Good and Alex Pretti.

Church World Service, a United Methodist partner in refugee resettlement, also demands change and accountability.

Claremont School of Theology in Los Angeles states that silence is complicity. The United Methodist seminary says it has students and alumni on the front lines dealing with immigration enforcement.

Immigration Law and Justice Network also condemned the killings and called for accountability. “We cannot call ourselves a democracy while immigration officials militarize our streets, kidnap immigrants and take the lives of those who are exercising their First Amendment rights,” the ministry said.

All people have a First Amendment right to record ICE or Border Patrol agents in public spaces, provided they do not physically obstruct their work.

“Usually that means staying at a distance (roughly 10 feet) and obeying orders to move for safety reasons,” Bowe said.

The Immigration Law and Justice Network offers the following guidance for what to do if you are:

Stopped on the street?

Ask “Am I free to leave?” Immigration enforcement is not allowed to keep asking you questions without reason. Before giving them your name or any information, ask if you are free to go. If they say “yes,” stay away from the place. If they say “no,” tell them you do not want to answer any questions and you want to talk to a lawyer. In some states, you may have to share your name, but that is it.

If ICE searches you or your belongings, you have the right to say: “I do not agree to this search.”

Stopped in a car?

Do not answer any questions related to your immigration status or your country of origin. Say: “I want to exercise my right to remain silent” and “I want to speak with a lawyer.” If the officer asks to search your vehicle, you have the right to refuse consent to any search. They cannot do it without a judicial warrant unless there is reasonable suspicion.

If you are driving along border states, Border Patrol could pull you over and you could encounter checkpoints. They can pull you over if they have reasonable suspicion of an immigration violation or a crime, and they may ask questions about your status. They can continue to detain you to inquire about your status, but they cannot force you to speak or to sign anything.

Facing ICE at the door of your home or facility?

Do not open the door. Federal agents theoretically cannot enter your home or facility without a judicial warrant. Also beware of sneaky tactics. Immigration enforcement often uses tricks to get you to open the door, so be wary of anything they say, the Immigration Law and Justice Network warns.

You have the right to ask to see the warrant. If the agents say they have a warrant, tell them to pass it under the door before opening it. If you are at the door of a facility, you can ask to review the warrant while they wait outside the front entrance.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

Check the warrant thoroughly. Confirm the name and address on the order to make sure it is precise to your location. Also verify that a judge has signed it. An ICE warrant is different from a court-mandated, judicial warrant. During raids, agents often say they have a “warrant” when all they have is an ICE warrant.

If in a facility, designate “private spaces” with closed doors. If ICE comes to your church or other facility, people inside have stronger privacy rights when out of “public spaces” like waiting rooms.

The United Methodist ministry also says what not to do.

- Do not run. If you run, federal agents may go after you.

- Do not show false documents, be it a fake driver’s license or other fake identification.

- Do not sign anything without the advice of an attorney.

Any of these actions could make an encounter go worse or result in more legal trouble.

This is a critical time for people of all faiths to be present with their immigrant neighbors and to bear witness to what is happening, said retired Bishop Minerva Carcaño, chair of the Council of Bishops Immigration Task Force.

“If we are startled by a government that is increasingly acting in authoritarian ways and outside the bounds of U.S. laws and policies, immigrants — even those who are in the U.S. legally — are living in extreme fear for their lives,” she said.

What is happening now reminds the bishop of when Christians needed to go into hiding during times of persecution when the Roman Empire saw Jesus’ teachings as threat to imperial rule.

“We United Methodists believe that we are called to live in and as witnesses of the boundless compassion, mercy, love and justice of the Kingdom of God inaugurated in Jesus,” Carcaño said. “This is the time to be faithful.”

Hahn is assistant news editor for UM News. Contact her at (615) 742-5470 or [email protected]. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free UM News Digest.