Key points:

- The women who were first through the door to become leaders in The United Methodist Church haven’t gotten the recognition they deserve, say two historians who’ve edited a book to start correcting that situation.

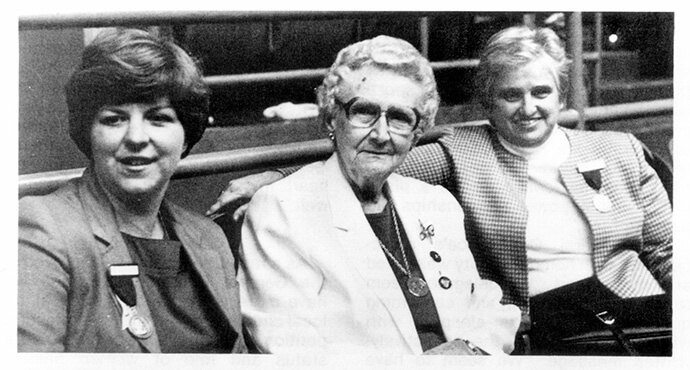

- “Southern Methodist Women and Social Justice” features profiles of Mary McLeod Bethune, Bishops Charlene Kammerer and Leontine T.C. Kelly and six others.

- The book was intended for classroom use but has fascinating stories that would appeal to more general readers.

Sometimes, even in happy moments full of affirmation, Bishop Charlene Kammerer feels a twinge of the pain from earlier in her career, when women leaders in The United Methodist Church faced serious roadblocks.

“There are times when something in the church, in a conference or in a gathering of friends, where I will be triggered of a memory that was very painful to me, and not me only, but other early women in ministry,” said Kammerer, the first female bishop in the Southeastern Jurisdiction, who served from 1996 to 2012.

At the Florida Annual Conference meeting in June, Kammerer had that feeling while addressing clergywomen at a breakfast meeting.

“I gave some examples of what life and ministry looked like and felt like in that first wave, which would be 1970 to 1980,” she said. “Many of the women there would not have similar experiences or know that those kinds of things happened.”

“Like what?,” you might ask.

That’s where a new book with a mouthful of a title — “Southern Methodist Women and Social Justice: Interracial Activism in the Long Twentieth Century” — can help. Written by an assortment of authors, it was edited by Janet Allured and M. Kathryn Armistead.

“Clergywomen described incidents of harassment and threats, including inappropriate comments about their bodies and clothing, similar to incidents that continue to this day,” write Jeanette Stokes and Fran Wescott in the chapter on Kammerer, though not referring to Kammerer personally.

“Congregants harassed women by making comments or posing questions such as, ‘Why isn’t a nice little lady like you married?’ Some women ministers were targets of unwanted sexual advances — grabbing, kissing and more violent attacks.”

9 women to know

“Southern Methodist Women and Social Justice: Interracial Activism in the Long Twentieth Century” features the stories of nine important Methodist women.

As horrible as that is, the problem has been much broader than that, Allured said in an interview with United Methodist News. For the most part, official Methodist history has been about men.

“Traditional church histories were male because men ran it, right?” Allured said. “For a long time, the women’s group in the Methodist Church, United Women of Faith and its predecessors, they used to make fun of it or say this kind of as a joke: ‘When are the women going to join the church?’ Because their women’s group was so separate, and so it’s really easy for people who are writing church histories, institutional or otherwise, maybe histories of pastors or bishops or whoever it is, those are going to be male.”

“Southern Methodist Women and Social Justice,” although intended as a book for students and academics, with a hefty price of $95, has a great deal of fascinating information for more casual readers. Published by the University Press of Florida, the cost will be less when a paperback edition comes out down the line.

The new book spawned from Allured’s 2016 book, “Remapping Second-Wave Feminism: The Long Women’s Rights Movement in Louisiana, 1950-1997.”

“I was doing research on that other book, about second-wave feminism in Louisiana,” Allured said. “I began to notice that many of the people who were part of the movement in Louisiana were Methodist, which was kind of surprising to me.”

Allured grew up Methodist, but as an adult joined the Episcopal Church.

“I hadn’t stuck around to be Methodist long enough to make the connection,” Allured said. “So I was like, ‘Wow, there’s something here,’ and then I decided to go down that rabbit hole.”

There are plenty of important stories about women and Methodism, and Allured is hoping “Southern Methodist Women and Social Justice” might inspire historians to bring more of them to light.

“From anti-racism, worker’s rights, equal housing opportunities, fair pay, economic justice, gender equality and bodily integrity, creation care, to ending mass incarceration and developing new models of leadership, Methodist women, rooted in faith, have expanded the vision for a better South, a better United States,” Allured writes in the epilogue of the book.

“I really want to encourage graduate schools to put their graduate students on it, because there’s so much material out there and all these archives,” she added in the interview.

“There’s a million dissertations out there, if you just want to deal with the women. But that’s not where people gravitate. It’s very unusual to have them gravitate to the women.”

Armistead, an author, scholar and United Methodist clergyperson, brought her knowledge of Methodist history to the project. She is the managing editor of “Methodist Review,” a journal for Wesleyan and Methodist studies. She noted that all of the subjects of the book “married their faith with politics.”

“That’s how they understand their faith, putting their love of God into action and through the political process to make a difference in our culture,” Armistead said.

“There’s always a lot of controversy whether the church should get mixed up in politics, but I think these women really show that sometimes that’s absolutely necessary to make the kind of changes that we believe are good for the world.”

The connection with issues outside of the church lent her individual story more resonance, Kammerer said.

“It was important to the co-editors, and it’s certainly important to me that the relationship between women’s struggle for full clergy rights and ordination and exercising ministry in the church did have some parallels with what was happening with the equal rights struggle and what was happening with civil rights,” Kammerer said.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

“Those were sometimes going in the same direction, but they were all acknowledged, and I think that’s important.

Asked about other Methodist feminists who might be ripe for scholars, she reels off a list.

“Honestly, I think there are dozens,” Kammerer said.

The first to come to her mind is retired Bishop Sharon Zimmerman Rader, today bishop-in-residence at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary.

“We were in seminary together at (Garrett), and she became a bishop a long time before I did, and she mentored me a lot at seminary.”

Kammerer said she observed closely as Rader preached, offered pastoral care and displayed leadership.

“I sat with her in meetings where I saw her spiritual leadership and that had a big imprint on me,” she said.

“There are a strong number of men who in the early years among ministry in Florida sought me out as a sister, friend and as a colleague, and have told me over the years that I had significant impact on their ministries,” Kammerer said.

But female mentors were critical, she stressed.

“We women, I think particularly early on, we couldn’t be fully validated in our call for exercise of ministry unless it was by other women,” she said. “We needed to see other women, to experience other women, to hear the stories, to support each other, to encourage each other.

“It only reinforced our calling when we knew that other women had been called as well, and it gave us a lot of courage along the way.”

Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or [email protected]. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.