Key Points:

- After a military coup forced him out of his native Liberia, United Methodist Bishop Bennie Warner needed to begin ministry anew in the U.S.

- He pastored churches in Oklahoma, New York and Arkansas, eventually retiring as a district superintendent.

- His resilience and faithfulness inspired a documentary.

United Methodist Bishop Bennie D. Warner had reached what many would consider his career pinnacle when a military coup upended his life and forever changed his ministry.

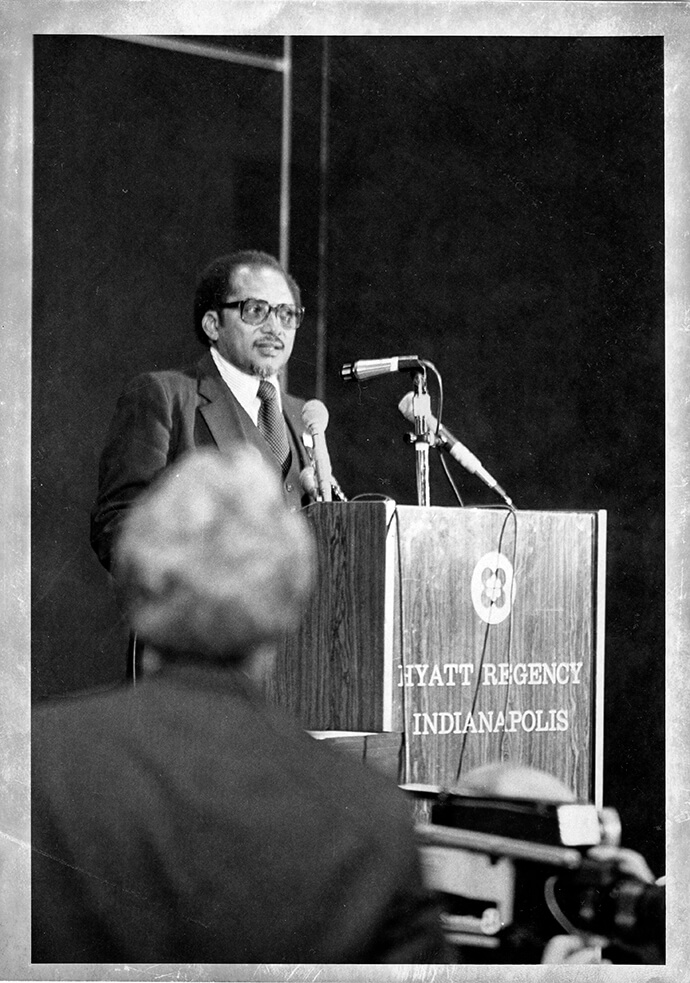

He was both bishop in Liberia and the west African nation’s vice president when in April 1980, the military overthrew the Liberian government and began executing the elected leaders. At the time, Warner was attending the Council of Bishops meeting just before that year’s General Conference in Indianapolis.

He soon learned he and his wife could not safely return home. So he began ministry anew in the United States, eventually retiring in 2004 as a district superintendent in Arkansas.

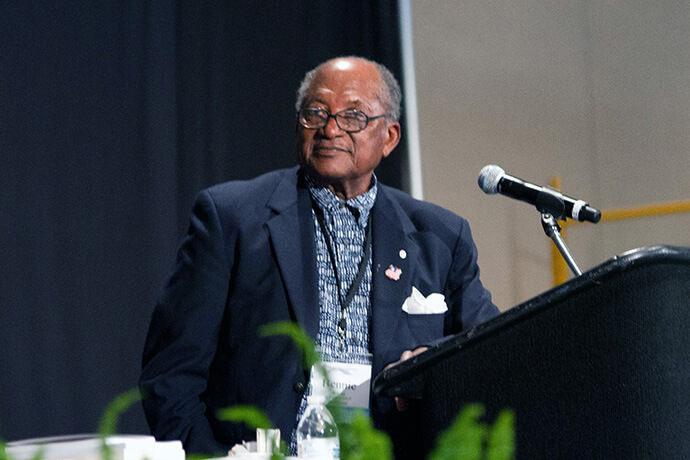

Warner, remembered for his faithful ministry and humility through rise and reversal, died Oct. 27 at age 89. A funeral and celebration of his life was held Nov. 23 at Wesley United Methodist Church in Oklahoma City.

“From the halls of power in Liberia to the backwoods of Arkansas, he certainly followed where God led,” said the Rev. Blake Lasater, who served under Warner as a young elder and now is lead pastor of First United Methodist Church in Eureka Springs, Arkansas.

“He is one of the wisest, most compassionate teachers I have ever known.”

The Rev. Bob Hager, a retired Arkansas pastor, was so impressed by Warner’s resilience and faithfulness that upon starting a second career as a videographer, Hager decided to make a documentary about the bishop’s ministry.

“His story was one of rags to riches to back to humble small-church pastor,” Hager said. “I felt like the church needed to have that sense that, if we’re really dedicated to live out the Gospel and we’re really dedicated to do God’s work, God can do some amazing things in our lives and the life of the church.”

Hager titled the 2013 documentary “Black Marks on White Paper,” taking inspiration from one of the late bishop’s fondest childhood wishes: To learn how to write.

Warner was born on April 30, 1935, in a remote village east of Monrovia, Liberia’s capital. In the documentary, he recalled a childhood memory of seeing town leaders writing on paper and reading the words they had written. The young Warner asked his father how he, too, might “put those little black marks on white paper, so I can tell people what it says.”

His father told him that the people who could read and write had gone to school. The problem for Warner was that his village had no school for him to attend.

When he was 15, he learned of a Methodist mission school being built in Gbarnga, several miles from his village. After he made the long journey, he immediately tried to enroll and the missionaries there asked him for tuition. Warner did not know what that word meant, and when told it meant money for school, he had to admit he had none.

So the missionaries, the Rev. Ulysses and Vivienne Gray, instituted what amounted to a work-study program, allowing Warner to attend class while also working as a school janitor. The Grays also became his guardians.

The commitment paid off. In 1956, he graduated at the top of his class from the Booker T. Washington Institute in Kakata, Liberia.

To watch

The hour-long documentary “Black Marks on White Paper,” is available to watch for free on Vimeo. The documentary was funded in part by a grant from the Methodist Foundation for Arkansas.

Bishop Bennie D. Warner was preceded in death by his wife: Anna; his daughters: Kaymah H. Warner and Mardea M. Warner and son Phillip Warner.

Warner is survived by his son, Bennie D. Warner Jr. (Cheri); grandchildren: Kaymah, Shamondre, Katelynn, Treshawn, Jeremiah, Aubriana, Bennie III and Torrance; nieces, nephews, cousins and a host of other relatives and friends.

From there, he went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in education from Cuttington University College in Suakoko, Liberia. With help from a denominational scholarship, he completed a master’s degree in educational administration at United Methodist-related Syracuse University in Syracuse, New York.

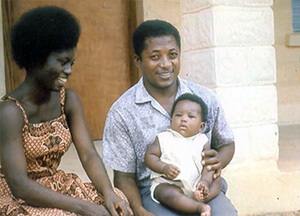

Degrees in hand, he returned in 1961 to Liberia determined to give back and teach at the same Gbarnga Methodist Mission where he had first learned to make “black marks on white paper.” He eventually became the elementary school principal and found another calling as pastor of nearby St. John Methodist Church. In 1963, he married Anna Harmon, with whom he shared 58 years of marriage before her death in 2022.

After years as a pastor, he decided he needed a seminary education to continue. In 1968, he and his young family moved to Massachusetts. He attended United Methodist-related Boston University School of Theology, where he graduated with a master’s degree in theology after majoring in Christian social ethics.

Back in Liberia, he continued his dual path as teacher and preacher. He was serving as religion instructor, counselor and chaplain at the College of West Africa in Monrovia, when what was then the Liberia Central Conference elected him as bishop in 1973. Warner became his nation’s 25th vice president in 1977.

Three years later, the coup left him without either office in his homeland and in need of political asylum, which the U.S. government granted. As the military took over, Warner recalled being told that if he came back, “There’s a machine gun with your name on it.”

With no episcopal assignment available in the U.S., Warner needed to begin United Methodist ministry again.

In “Black Marks on White Paper,” Warner said that he heeded the advice of a friend who said upon his election as bishop and vice president: “Don’t wear your jacket too tightly because it will be difficult to take it off.”

With that guidance in mind, he said he wore his august positions loosely. “So when they came off, I had no problem,” he said.

After seeking God’s guidance, he began to see himself as a missionary to the United States. Still, he continued to pray for the people of Liberia as coup eventually gave way to civil war.

Meanwhile, Warner and his family moved to Oklahoma City, where he taught at United Methodist-related Oklahoma City University and pastored Quayle United Methodist Church. He then served Faith United Methodist in Syracuse, New York, for two years before deciding to return to Oklahoma because he and his wife were weary of the extremely cold winters. But before making the move, Bishop Richard Wilke, then leading United Methodists in Arkansas, asked him to consider an appointment near Little Rock.

Wilke’s invitation brought him to St. Paul United Methodist, a historically Black congregation in Maumelle, Arkansas, that grew under his leadership.

Bishop Janice Riggle Huie, Wilke’s successor in Arkansas, asked Warner to serve as district superintendent on her cabinet.

Huie, now retired, said she was impressed at how he adapted to Arkansas life. There, he was not known as bishop but rather “Brother Bennie.” He also evangelized for the faith with gusto at one of Arkansans’ most frequent destinations: Walmart.

“He was a humble soul,” she said. “He’d been a bishop. He’d been important enough in his own country that they tried to kill him. And, here he was going out to the Walmart parking lot to invite people to visit a United Methodist church.”

Nevertheless, his time as superintendent brought unique challenges — especially in a state still wrestling with a history of segregation and at-times violent racial discrimination.

Lasater, serving his first appointment out of seminary in Warner’s district, invited the bishop-turned-superintendent to lead a revival at the tiny country church. But members of the community told him in no uncertain terms that a Black man would not be welcomed — even the district superintendent.

Ultimately, with Warner’s steadfast support, Lasater carried out the revival as planned with the district superintendent leading the service. Warner also had a surprise in store for the small church: He had invited members from surrounding Arkansas United Methodist congregations to attend. The result was a crowd that overflowed outside of the church doors.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

“It was an absolutely fantastic worship experience,” Lasater said in the documentary. “And it changed a lot of hearts because the people of Buena Vista saw so many people in our connection coming out to support Bennie but also to support the dream God has for the church.”

Lasater also shared with United Methodist News that when Warner eventually left south Arkansas, “every customer at Walmart said they would miss this man who for some reason loved to stand outside the store and tell them how much God loved them.”

Retired Bishop John Innis, who led the Liberia Conference from 2000 to 2016, regarded Warner as a mentor.

“Bishop Warner was very, very committed to Liberia,” Innis said. “He was a great motivator who worked to develop the youth of the country and make sure the church was well-equipped.”

That legacy continued even as war separated Warner from his homeland. Innis accompanied Warner when at last he could visit Liberia again in 2009. Warner came at the invitation of fellow United Methodist and then-President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, who would go on to win a Nobel Peace Prize.

In 2009, Warner delivered the opening sermon at the Liberia Annual Conference. “Everybody was very happy for his return to the country,” Innis said. “So it was excellent.”

Hahn is assistant news editor for UM News. Contact her at (615) 742-5470 or [email protected].To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Friday Digests.