Key points:

- An annual journey to learn about Native American culture and history covered more than 500 miles in Oklahoma.

- A group of students, United Methodist church members and pastors toured the First Americans Museum, where they saw hundreds of artifacts and exhibits featuring Indian drums, games and stereotypical misrepresentations of Native culture.

- One participant in the Oklahoma Indian Missionary Conference Immersion Experience offered an apology to a Native American educator.

Yewon Park’s feet provided some welcome levity as a group of United Methodists immersed themselves in Native American culture and reckoned with injustices the first Americans suffered.

“You’ve got little feet!” said Henrietta Mann, an accomplished academic and Cheyenne prayer woman, while performing a “smudging” ceremony on Park.

“Wonderful little feet!”

The comment cracked up the solemn group at the Clinton Indian Church and Community Center, Park included. Earlier that day, they had toured the Washita Battlefield National Historic Site, where Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer led a slaughter of 200 Native Americans, most of them women and children, on Nov. 27, 1868. Six hundred horses kept by the Natives were also killed, and the composition of the soil where it happened is still affected by the blood that was spilled.

The battlefield had an eerie, haunted aura, especially at a sacred tree where the group tied colored ribbons to show respect for the victims. Some people claim to have heard the voices of children playing there, believing it is their ghosts.

“It’s not a fantastic story,” said Kate Roesch, a park ranger in charge of education at Washita. “But it’s an important story. It may help it not happen again.”

Smudging is a Native American ceremony intended to cast out negativity while also putting protection around a person to ward off threats. A feather bathed in the smoke from burning sacred herbs is tapped on various parts of the body, with an emphasis in the area of the heart.

Park, a student from South Korea at Boston University School of Theology, was one of eight participants from the university taking part in the five-day Oklahoma Indian Missionary Conference Immersion Experience. In addition to students, the group of almost 30 included pastors, laypeople and church officials. Most were United Methodist.

The group traveled more than 500 miles in central Oklahoma over five days with hundreds of tall, white, tri-pronged windmills as the main attraction along the interstate highways.

Stops included museums, modest United Methodist Indian churches and battlefields — or massacre sites, depending on a person’s interpretation of the history. In addition to Mann, they heard from Native American United Methodist pastors, tour guides and a child psychologist who spoke about the abuse suffered by Native American children at boarding schools.

Bishop David Wilson visited the group March 11 at Mosaic United Methodist Church in Oklahoma City. The first Native American bishop in The United Methodist Church, Wilson now oversees the Great Plains Conference.

He said in his role as assistant to the bishop in the Oklahoma Indian Missionary Conference, he was involved with the immersion experience since the beginning, noting that the event grew out of a study on missionary conferences.

“There would be individuals who would come to OIMC just for teaching, just to learn about OIMC.”

He said organizers built on that connection, seeing the event as a way to welcome people and engage with them about Native experiences and issues.

“People enjoy learning and seeing more and just appreciate the experience,” he said.

The hope is to continue to engage with people about Native American history and concerns, said the Rev. Donna Pewo, director of connectional ministries for the conference and primary organizer of this year’s excursion.

“We're hoping to make connections with non-Natives, with other conferences and other individuals who have an interest and yearning to learn about our Native people and (Oklahoma Indian Missionary Conference),” she said.

“How can we network together, how can we learn about one another and engage and move forward in a way where we can respect and honor each other's opinions and way of living?

“And to let the world know that we are not invisible.”

The Rev. Nancy Tomlinson, district superintendent of the Blue River and Elkhorn Valley districts of the Great Plains Conference, said she had trouble working out why Native Americans were so welcoming of the group.

“I don't know that I understand how a people who've lost 99.994% of their people can even live in the world with the rest of us while looking at us and knowing that probably those of us with white skin of European descent are a part of the peoples who inflicted such harm and death upon them and their families,” Tomlinson said.

She said she doesn’t know that true repentance can come without the willingness to do some form of reparation.

“It feels like cheap grace. So I'm having an internal struggle on, ‘Hey, what does repentance look like when land has been stolen and lives have been taken?’” Tomlinson said.

At the First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City, a 175,000 square-feet facility that opened in 2021 with exhibitions of Native American history, culture and art, the group learned about famous Native Americans such as humorist Will Rogers, baseball player Johnny Bench and musician Jesse Ed Davis.

Participants played life-size video games to learn about Native American sports and saw exhibits — on loan from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian — on Native American drums and artifacts from the 39 tribes in Oklahoma.

A display of products using stereotypes to sell products included a cigar store Indian, a book titled “Bugs Bunny and the Indians,” Land O Lakes butter packaging using Native imagery and advertisements portraying Native women as one-dimensional sexual objects.

In the museum, “everything is told in the first person,” said Ginny Underwood, marketing and communications manager for the First Americans Museum. That approach is intended to recapture the narrative from the inaccuracies with which Native Americans have been portrayed in the media, she said.

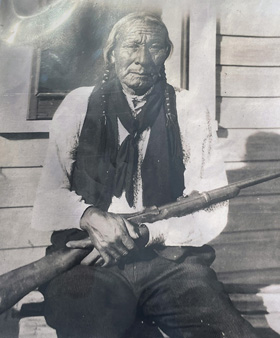

Back at Clinton Indian Church and Community Center, Mann spoke about the Battle of Sand Creek in 1864, also considered a massacre by many. In that clash, Col. John Chivington, a Methodist pastor, oversaw an attack on a Colorado village of Cheyenne and Arapahos, killing about 150, again mostly women and children.

“America has a way of forgetting the kind of brutality they inflicted on the people who lived on that land. I wish I could forget that my beloved ancestors were treated as brutally and savagely as they were,” Mann said.

“(Chief) White Antelope, he was scalped and his genitalia was cut from his body,” she said. “Like others who were mutilated in very horrible ways, the soldiers eventually made tobacco pouches from them, headbands for their hats and used them for decoration on their rifles and saddles.”

Such anecdotes appalled and shook the OIMC Immersion Experience participants.

“The whole situation is really sad for me,” said Ebiye Seimode, one of the Boston University students on the tour. “I haven't really processed the whole grieving, mourning part involved, like the massacres that happened.”

A native of Nigeria, Seimode said she has been in “war situations, me and my family running for our lives.”

“I hate to say it feels a little normal to me. … Right now, I think I'm just trying to learn as much as I can and then process later, because it is a lot of material and it is kind of overwhelming sometimes.”

Another student, Alec Vaughn, said he hoped to be a changed person through the experience of learning American history that is not often taught.

“What am I going to carry with me from this that I can do in my everyday life?” he said. “How am I going to treat people? When I hear an offhanded comment, am I going to say something or just let it slide?

“I mean, we need to stick up for one another, especially those of us seeking to be holy people,” Vaughn added. “To be closer with God, we need to be the change we wish to see, as Gandhi said.”

The Rev. Kathleen Wilder, a participant and senior pastor of Lafayette Park and Centenary United Methodist churches in St. Louis, said she is grateful for the opportunity to learn and grow in her faith.

Addressing Mann after her presentation, Wilder said, “A lot of Christianity is never what the Creator or the Savior wanted. It is institutionalized crap. My experience from listening to you opens my faith connected with the Creator in a deeper way, and I thank you for that.

“I repent of the sins that have been done to your community under the name of Jesus Christ.

“I'm sorry.”

Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or [email protected]. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.