When football season arrives, the Rev. Caesar Rentie gets restless.

He remembers working himself into top shape so he could knock other large men around as an offensive tackle, including for the Chicago Bears.

“It’s always in my blood,” Rentie said of football.

These days, he does very different work, serving as vice president for pastoral services at Dallas-based Methodist Health System and associate pastor at First United Methodist Church in Mansfield, Texas.

While there are a few former NFL players in ministry, Rentie knows of no others in hospital chaplaincy. If this weren’t distinction enough, he’s also a CODA — a child of deaf adults.

Football gave Rentie a college education and helped move him out of poverty. Growing up with deaf parents taught him to read body language closely.

That’s a plus for a chaplain.

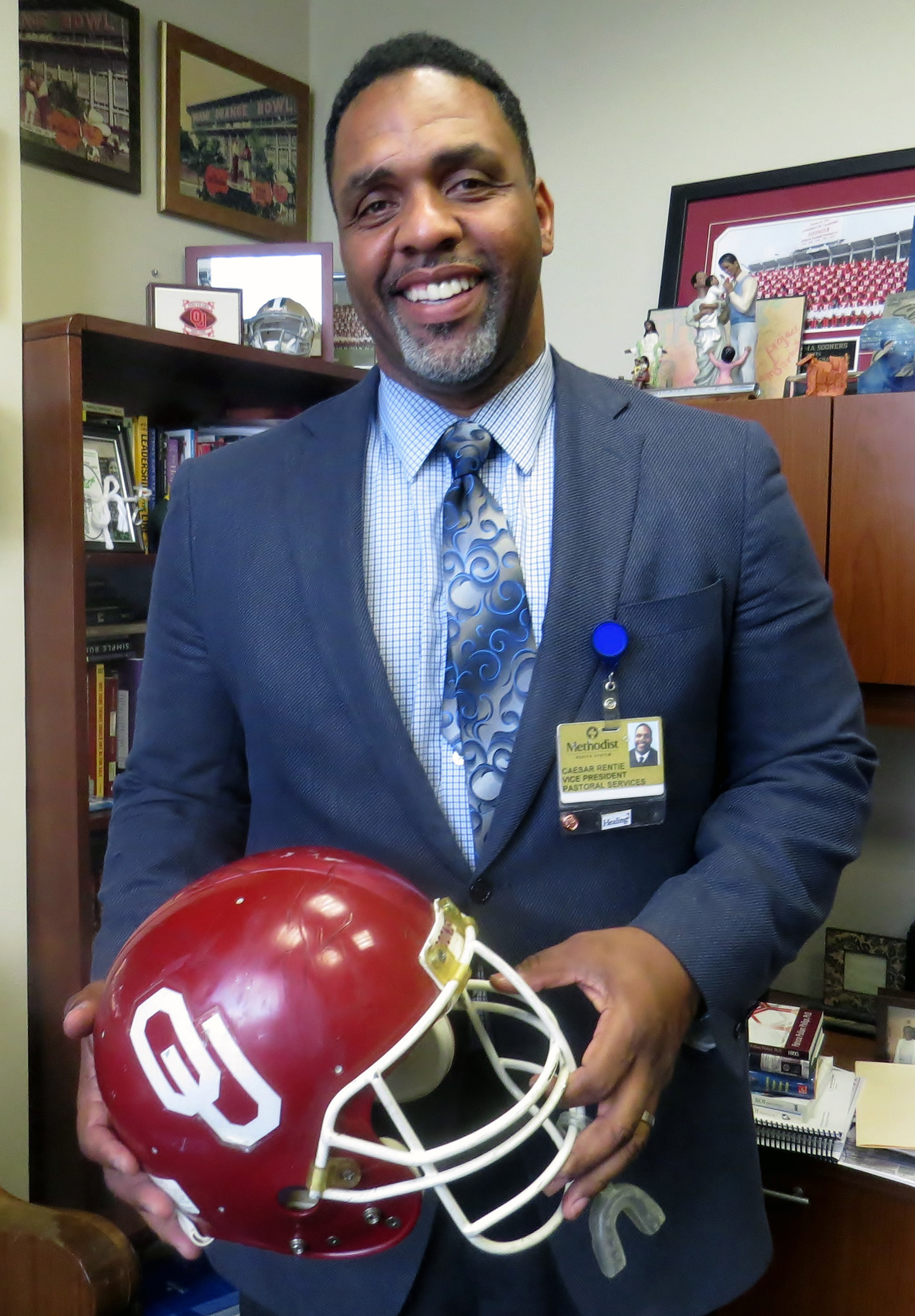

The Rev. Caesar Rentie, vice president for pastoral services at Methodist Health System in Dallas, holds a helmet from his days as an offensive tackle for the Oklahoma Sooners. Rentie likes to say he’s available for counseling to University of Texas fans whenever their school has to play Oklahoma. Photo by Sam Hodges, UMNS.

“You learn nuances,” he said. “When I walk in the room … I get a sense of what this person is feeling.”

At the hospital, Rentie stands out for his size (6 feet 2 and ½ inches tall, and 275 lbs.) — and for his character.

“We feel like Caesar Rentie is one of God’s many blessings on Methodist Health System,” said Stephen Mansfield, president and CEO. “He is humble, gentle, kind and reflects our Christian values in his walk among us.”

Rentie, 52, grew up in Kansas, Texas and Oklahoma, and, like his siblings, can hear. But with deaf parents, he learned American Sign Language as a toddler. Even now, his hand gestures involuntarily form signs.

At a school for the deaf, his father trained to be a cook and his mother a seamstress. But when his father lost a leg to diabetes and couldn’t work, the family’s finances collapsed.

Rentie recalls times when the lights and water at their Hartshorne, Oklahoma, home would get turned off.

“There was always more month than there was money,” he said.

Dr. Brad Luckett, a dentist and Fellowship of Christian Athletes leader in the town, remembers how little the Rentie family had.

“Their food was beans and cornbread,” he said. “Their roof leaked so bad that Mrs. Rentie didn’t have enough pots and pans to catch the water.”

But in Hartshorne, Luckett and others took an interest in Rentie, who was notable for his athletic ability and light-up-a-room smile. He was a big kid with a big appetite, too.

“My wife baked pies, and Caesar would eat a whole pie,” Luckett said.

Though at a tiny high school, Rentie made national football recruiting lists. He signed with Oklahoma University, playing four years under Coach Barry Switzer, including on the 1985 national championship team.

Rentie was unprepared for college studies. But he followed Luckett’s advice to go to every class, pay attention and befriend whichever student seemed to be taking the best notes.

He became his family’s first college graduate.

“When I think about college and what makes me proudest, it’s not the national championship. It’s the day I graduated,” Rentie said, choking up. “My parents were in the stands.”

In 1988, Rentie was a seventh round draft choice of the Chicago Bears, and made the team. He weighed about 290 pounds, but in practice lined up against 350-pound William “The Refrigerator” Perry.

Rentie saw action in five games that season. The next season, he signed with the Buffalo Bills, but got cut. His other efforts to play for an NFL team failed, so he moved to the World League of American Football. He made a name there.

“Steady, consistent, productive, and a fantastic teammate,” said Joe D’Alessandris, his line coach with that league’s Birmingham Fire, and now a coach with the Baltimore Ravens.

After playing football, Rentie became a graduate assistant coach at Texas Christian University. He also joined Dallas’ St. Luke Community United Methodist Church.

The church’s famed pastor of the time, the Rev. Zan Holmes Jr., heard Rentie speak at a Men’s Day service and encouraged him to consider ministry.

“God is certainly not calling me,’” Rentie recalled thinking.

But after a year, he decided otherwise and entered TCU’s Brite Divinity School. There, in a basic pastoral care course, a professor saw in Rentie the makings of a good chaplain. The professor urged him to take clinical pastoral education or CPE.

Rentie signed up, doing his internship at Methodist Health System’s Dallas hospital.

“I remember meeting my first patient,” he said. “I knew that’s where I needed to be. It was kind of like I found home, and I’ve been here ever since.”

Rentie is endorsed by the United Methodist Endorsing Agency, which supports chaplains and pastoral counselors serving beyond the local church. A longtime fellow chaplain at Methodist Health System, the Rev. Mary Stewart Hall, remembered concluding early that Rentie was in the right line of work.

She said a young male patient had both serious medical issues and deep anger that caused him to reject help from chaplains. Rentie wouldn’t quit.

“Caesar in his quiet, persistent way built a relationship with this young man, as only Caesar could,” she said.

Rentie spent much of his early chaplaincy working long weekend shifts, including many visits to the emergency room. He acknowledges being shaken by the suffering he saw.

One evening about 2 a.m., a young man was brought in with a gunshot wound to the head. Rentie had to call the mother, who drove through the night from Arkansas. He stayed at the hospital to meet her, and was with her when her son was declared dead.

Rentie also stood by as an organ donation representative talked to the mother. She chose to donate all possible organs from her son.

Soon Rentie was watching as doctors removed the organs, the last being the heart. Rentie released the body to the medical examiner.

“I felt like the guardian,” he said. But he also recalled feeling heartbroken and questioning both his faith and vocation.

A few months later, Rentie was asked to offer a prayer at an organ donor-recipient luncheon. He heard a recipient speak on what a difference his new heart had made. The man shared about meeting the donor’s mother, and how she asked to put her head to his chest, so she could hear her son’s heart keeping someone else alive.

Then the mother in question stood at the luncheon, and Rentie realized that she was the woman he’d counseled at Methodist.

Rentie felt confirmed in his faith and work.

“The message that came to me and helped me reconcile with the suffering was that it was my role to be here, to be a presence, to offer care, spiritual and emotional, not only to patients, but to staff and families,” he said.

For 25 years, Rentie has done that. He’s climbed the ladder at Methodist, and now supervises pastoral care at three Dallas-area hospitals.

He’s also a licensed local pastor and at First United Methodist in Mansfield oversees the Celebrate Recovery ministry for people with addictions.

Community outreach is part of Rentie’s work, and he’s a popular speaker. He has preached at Highland Park United Methodist — one of the denomination’s largest churches — and recently addressed the Global Methodist Missions Conference of the Deaf.

His sign language was rusty, but he was a hit, with many of those attending wanting to have their picture taken with the former NFL player.

“I told Caesar he’ll always have a deaf family,” said the Rev. Tom Hudspeth, organizer of the conference.

Rentie recalls that even as a boy he felt protective of his parents. Later, he would block for running backs and quarterbacks, trying to keep them out of harm’s way.

Chaplaincy, he’s come to understand, is another unspooling of a long thread.

“This may have always been inside of me,” he said, “that need to serve and protect.”

Hodges, a United Methodist News Service writer, lives in Dallas. Contact him at (615) 742-5470 or [email protected].

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.