One of the biggest health risks United Methodist clergy face boils down to one word: stress.

Too many church potlucks, pizza-delivery nights and meals on the run are not helping.

Those are two implications of a study of clergy physical, emotional and spiritual health released this month by the Center for Health at the United Methodist Board of Pension and Health Benefits.

The February online survey of nearly 2,000 of the denomination's active U.S. clergy found that ministers reported engaging in more physical activity than their U.S. peers. They also report getting a comparable amount of sleep - a little more than seven hours each night.

Yet, they still reported a higher incidence of health problems.

Specifically, those who responded experience obesity, high cholesterol, borderline hypertension, borderline diabetes, asthma and depression at significantly higher rates than do other demographically comparable U.S. adults.

The clergy calling "is a tremendous blessing, but it also exacts a price," said the Rev. Charles Reynolds, executive director of Virginia Conference Wellness Ministries Ltd., which helped design and fund the study. The Duke Clergy Health Initiative and the Duke Center for Spirituality, Theology and Health also assisted.

"Ministry is a vocation where you're never going to get everything done that should get done or could get done or that you feel you should do," he said.

More than half of the clergy - 58 percent - reported they often experience at least one type of occupational stress. Such stress, Reynolds pointed out, can lead to overeating and a variety of medical issues including clinical depression and asthma attacks.

He expressed hope that the study would lead to intentional efforts churchwide to help reduce stress and help clergy practice healthier habits including self-care.

"Improving clergy members' diet and nutrition is key," the study says. "Depression is also an area of risk. Contributing factors may include relationship with congregation, stressors of the appointment process, work/life balance, job satisfaction and marital and family satisfaction."

Study findings

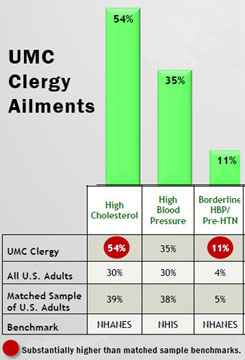

Excerpt from the May 2012 Report of Findings from the 2012 Annual Clergy Health Survey. A web-only chart courtesy of the United Methodist Board of Pension and Health Benefits. View full chart

The 2012 study is the first planned annual study on U.S. clergy well-being, said Anne Borish, the Center for Health's research and information manager. The survey respondents included elders, deacons and local pastors. It also was representative of U.S. clergy based on jurisdiction, gender, age and racial-ethnic group.

It follows up on last year's Church Systems Task Force report that offered recommendations for improving clergy health.

"Now we have an effective baseline to track what we hope will be good progress over time to addressing the health issues," Borish said. "We believe we need healthy clergy and healthy congregations; one benefits the other."

She acknowledges many clergy have some work to do to meet national benchmarks.

The study compared the United Methodist clergy results to demographically-matched samples of U.S. adults in the 2010 National Health Interview Survey and the 2009-10 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sponsored both national health surveys.

Among the 2012 findings:

- 54 percent of clergy have high cholesterol, compared to 39 percent of the matched sample

- 41 percent are obese, as measured by their body mass index, compared to 32 percent of the matched sample

- 16 percent experience asthma, compared to 10 percent of the matched sample

- 11 percent have borderline hypertension, compared to 5 percent of the matched sample

- 28 percent have some functional difficulties due to depressive symptoms, compared to 12 percent of the matched sample

- 6 percent suffer from depression, compared to 3 percent of the matched sample

On the positive side, United Methodist clergy also reported engaging in four hours of physical activity per week, while the matched sample reported two hours. The clergy also reported participating in vigorous activity such as running, aerobics and heavy yard work more often than their peers did - nearly two hours compared to 97 minutes.

Borish credits annual (regional) conference walking programs with helping to get preachers out of their clerical collars and into their exercise gear.

"It's great that we have levels of physical activity that beat the norm," she said. "But it's not nearly enough."

Differences among clergy

The study also identified differences among the demographic sectors of United Methodist clergy.

Clergy at smaller churches have higher physical health risks, while those at larger churches have higher spiritual health risks and occupational stress risks. Clergy who change appointments more often show higher levels of risk across all health dimensions.

White clergy, especially white men, score lower on spiritual health measures, such as feeling God's presence in church events and daily life. African-American clergy have a higher risk for hypertension and for being overweight, but they also have lower rates of depression and report less stress. Asian-American clergy have a lower risk on several health measures, including weight, arthritis and asthma.

In the future, Borish said the Center for Health would like to expand its focus to clergy health issues that are most germaine to the central conferences - church regions in Africa, Asia and Europe.

Systemic changes for health

Improving clergy health takes systemic change too, said the Rev. Charles Reynolds and others who served on the Church Systems Task Force.

The recently concluded 2012 General Conference, the denomination's top lawmaking body, began some of these systemic changes, adopting five of the task force's petitions.

The changes include:

- A requirement for immediate resolution of parsonage issues that affect family health

- The use of mentors for clergy separate from district superintendents

- A streamlined definition of a district superintendent's role

- A Clergy Indebtedness Task Force

- A Voluntary Transition Program to provide pay and benefits for clergy exiting ordained ministry

General Conference also adopted a related petition from the United Methodist Board of Discipleship that requires staff-parish relations committees to work with pastors in work-life balance and personal wellness.

Reynolds said one contributor to some clergy health problems might be the itinerant system itself.

"Among a lot of clergy and their spouses," he said, "there's still a feeling that the itinerant system does not take adequate notice of the careers of spouses, the emotional needs of children and where the children are in the educational process."

He supports itinerancy, but he hopes bishops and appointive cabinets keep such considerations in mind. Whatever stress clergy feel, he said, research in Virginia has shown that spouses and children often feel it even worse.

How one pastor lost 200 pounds

The Rev. Richard Richter, the pastor of Hillcrest and Hendron's Chapel United Methodist churches in Knoxville, Tenn., can attest to how the stresses of ministry can lead to poor diet and unhealthy habits .

"As a pastor, I can't drink; I can't smoke; I can't do drugs, but they certify eating at church," he said. "Some people would crawl into a bottle and die. I would crawl up into a vat of mashed potatoes and die."

He does not know his top weight. He stopped checking in 2003, when a scale showed he weighed 440 pounds.

That started to change with a radio station's contest in 2007 that enabled Richter to work with a personal trainer. He started with pool exercises and time on a cross-training machine. His trainer eventually introduced him to a "spin" indoor cycling class. After eight weeks with the trainer, he continued spin classes, bike riding and other physical activities.

Between 2007 and 2010, he estimates he lost at least 200 pounds. At 49, the 6'2" pastor now weighs 240 pounds.

Still, he acknowledges, making the time to exercise and eat right remains a challenge.

"Everything about being the clergy draws you away from taking care of yourself and toward taking care of somebody else," he said.

But he now forces himself to exercise, typically arriving at the Y at 5:15 a.m. on weekdays. Sometimes, he'll even drive hours away to the YMCA in Cleveland, Tenn., where he started his exercise regimen.

"It's like going to chapel without responsibility," he said. As music thumps and stationary bicycle wheels spin, he is not only burning calories. He is also talking with God, confessing his shortcomings from the previous day and giving thanks for the day ahead.

Richter and others agree it's important to practice the spiritual discipline of Sabbath, to take a break from the usual pastoral duties of hospital visits, church meetings, counseling sessions, administrative tasks and worship preparation.

The Rev. Clarence Brown, who has served as a district superintendent and now is senior pastor of Annandale (Va.) United Methodist Church, said he sometimes tells parishioners he has an appointment to keep, and it's an appointment for himself and his family.

As Psalm 46 says, sometimes it's enough to be still and know God is in charge.

"If you're not good to yourself, you're not good to anyone," Borish said. "Sometimes, that's a hard lesson."

*Hahn is a multimedia news reporter for United Methodist News Service.

News media contact: Heather Hahn, Nashville, Tenn., (615) 742-5470 and [email protected].

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.