Since the 19th century, The United Methodist Church has developed ministries with the Hispanic/Latino community. More than 200 years ago, the Methodist Episcopal Church and the Methodist Episcopal Church South began working in areas of the United States where the Hispanic population is most concentrated (Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Pennsylvania and Texas).

Many of the ministries grew into congregations and missions. However, no coordination, joint efforts or resources existed.

In the second half of the 20th century, the church created institutions to work in coordination with various aspects of ministry in the Hispanic community.

- The Spanish Resources Committee, composed of representatives from various general agencies

- La Junta Consultiva de Comunicaciones, an advisory board under the United Methodist Commission on Communication, which produced El Intérprete magazine

- MARCHA, the Hispanic caucus within The United Methodist Church.

These three entities paved the way to what we know today as the National Plan for Hispanic/Latino Ministry. The Rev. José Palos was the founding director. In 2012, the National Plan celebrated its 20th anniversary. In honor of that landmark year, Palos published a brief history of the plan.

In celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month, we combined segments from Palos’ book with his interview responses, editing some copy and remarks for space and clarity.

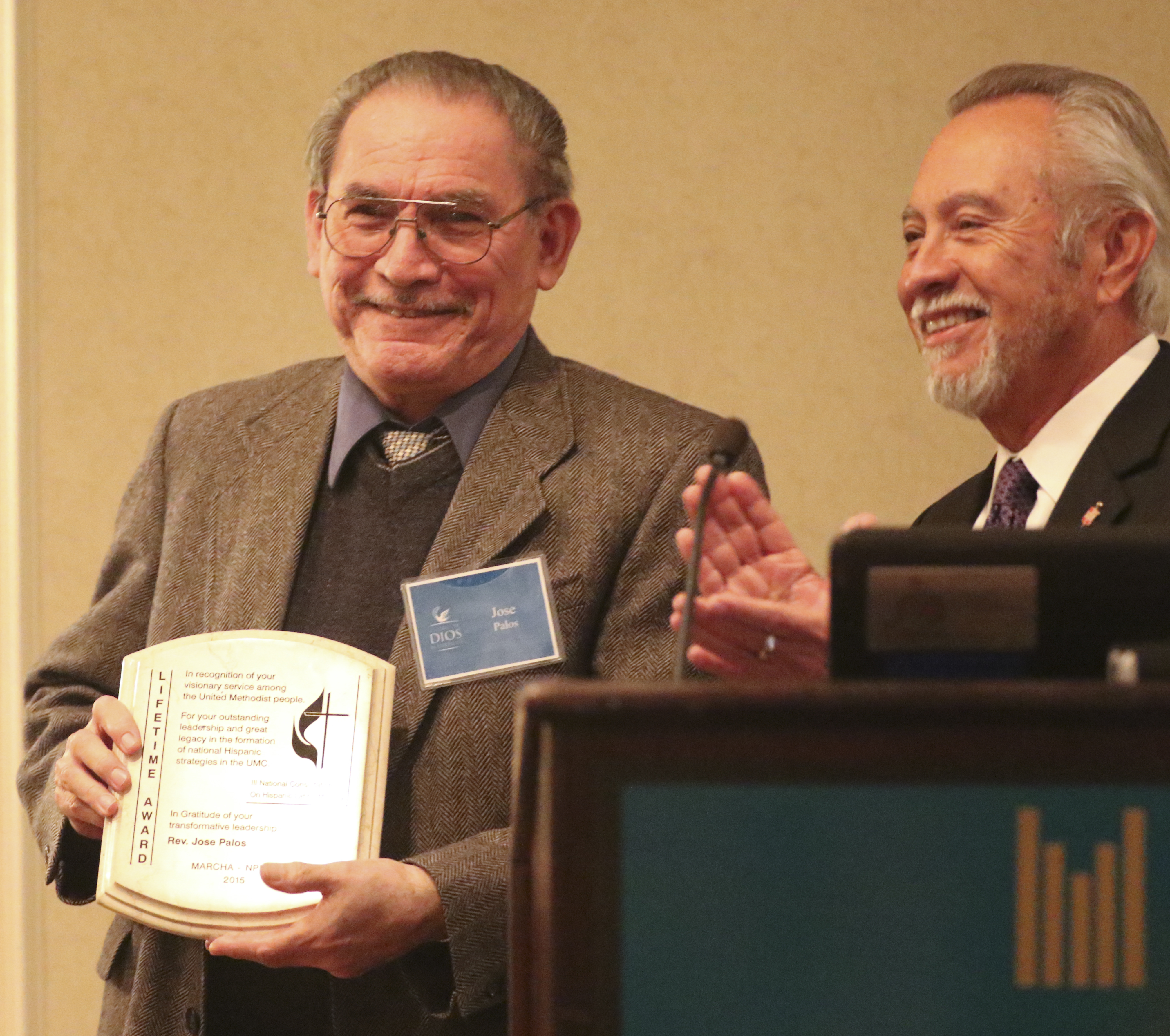

The Rev. José Palos, founding director of the National plan receives a recognition award at the third National Consultation on Hispanic/Latino Ministry on March 12-14 at Duke Divinity. Presenting the award is Bishop Elias Galvan. Photo by Rev. Arthur McClanahan, Iowa Conference

Describe the origin of the National Plan and its first two decades of work.

The approval of “Developing and Strengthening the Ethnic Minority Local Church” as a United Methodist missional priority was an important precedent that helped Hispanic/Latino leaders know each other better and work together.

In the 1980s, after a national consultation on Hispanic/Latino ministries, the National Committee on Evangelism and Congregational Development, which I chaired, was formed. This committee held several regional and national trainings on Hispanic ministry; several United Methodist general agencies supported this initiative with personnel and funding.

Bishop Joel Martinez, who was a member of the United Methodist Board of Global Ministries, played a role in that moment. He had the initiative to promote meetings and provide contact between the U.S. United Methodist conferences near the [U.S.-Mexico] border and the Methodist Church of Mexico.

In 1987, the MARCHA Strategy Committee, along with general agency Hispanic staff, discussed the idea of submitting to the United Methodist General Conference a request to develop what would become the National Plan for Hispanic/Latino Ministry.

The 1988 General Conference approved a study committee, coordinated by Bishop Elias Galvan, to yield data and opinions about the Hispanic people, how to minister to them and how to develop a national plan. A subcommittee drafted the first version of the plan to send to the next General Conference.

Although the 1992 General Conference approved the plan, it had no resources for the first four years. The committee barely had funds to cover its expenses and production of some Spanish resources.

Pastors and conference leaders actively participated in discussions and promoted the idea of a coordinated effort, but the concept of a plan was rather a response from the general agencies seeking to join forces, share resources and be more efficient in promoting ministries in the Hispanic community.

What issues did leaders discuss? How did they visualize the future of the Hispanic ministry of The United Methodist Church?

There were two specific emphases: first, the development of new ministries at the local level, both congregational and community service; and second, leadership training for work in the church. We needed to develop both aspects from our realities and our culture:

- We are smaller communities whose faith is not predominantly Wesleyan, or even Protestant-evangelical, and are very unstable to settle permanently in a given site.

- We do not fit the assumption that a new congregation’s economic capacity will be self-sustaining within three to five years. This does not work in the Hispanic and immigrant population because we are a working community with low incomes and we relocate constantly looking for better job opportunities.

- Very few Hispanic faith communities have the ability to pay pastoral services under the standards of the Anglo church.

- Theological programs and education have an Anglo-centric profile and lack the multicultural vision necessary for working with the very diverse Hispanic community.

One of the biggest obstacles, which still exists in some areas, was that annual conferences zealously maintained their own procedures. When opening new Hispanic ministries, conferences were pressed to get clergy leaders. Since the formal system was not offering them suitable candidates, they hired people just for being Hispanic. [These people] often lacked skills, theological training and the Methodist doctrinal tradition.

The only time there was a coordinated jurisdictional effort was from 2008 to 2012 when the Western Jurisdiction formulated a strategy to improve the recruitment process and clergy training for Hispanics among all conferences in that jurisdiction.

The plan made several proposals seeking to improve the situation. One, geared toward conferences with a high concentration of Spanish speakers, asked that clergy be required to learn Spanish so they could minister in any language to any church. Conference boards rejected this proposal.

What were the biggest challenges and resistances?

Challenges included:

- Developing Spanish resources to train lay leaders

- Developing new ministries

- Revitalizing established congregations

- Helping churches made up of different cultures to develop ministries for the Hispanic community

- Preparing pastors for emerging churches and congregations. The traditional system makes it difficult for an immigrant who comes from another culture and speaks another language to gain access to the required academic training in order to be considered and recognized as clergy.

Many churches and faith communities kept fighting against the odds generated by the structure of the church. For them, the plan represented a platform that would give them more visibility and a voice within the rest of the church so they could further the development of Hispanic ministries. We found resistance to participate in the national plan from annual conferences that had already established Hispanic ministries.

We also realized that some Anglo conference leaders initially expressed interest when made aware of the existence of funds that would enable them to unload expenses related to Hispanic ministries. When funds were unavailable, for some, the interest disappeared.

Another concern was how to address and minister to the social problems facing the Hispanic population, many of which remain today. Immigration is an example. The United Methodist Board of Church and Society directly advocates among politicians in Washington. The plan’s proposal was to work also with community leaders, pastors and grassroots groups. The two methods are not always compatible.

How do you view the plan today and envision its future?

The obstacles still interposing the structure of the church are issues like congregational development and clergy training. I am not sure of how the plan is dealing with the limitations we had with the governing congregational development system, but it is certainly an ongoing challenge. I get the impression that there is still reluctance to change the preset ministry models and that there is still no coordinated system between conferences in recruiting and training pastors.

One of our past shortcomings was the lack of criteria and an appropriate mechanism for assessing and monitoring ministries at local and regional levels. I hope we are overcoming this.

Overall, the plan has evolved well. We now have more Hispanic/Latino staff at the national level. Several missionaries work in different important topics for the life and development of Hispanic ministries, and this is very positive.

Hispanic churches and ministries have grown across the United States. What has been done through the Path 1 program [Discipleship Ministries] has been very positive overall. This leads to the need for developing strategies to monitor and support further development and faster, broader growth.

Vasquez is director of the Hispanic/Latino Communications, United Methodist Communications in Nashville, Tennessee. Michelle Maldonado, associate director of Hispanic/Latino Communications translated and adapted this story. Contact Vasquez at [email protected], 615-742-5400.

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.