The Rev. Orlando Gallardo Parra was 15 when his mother decided it was worth the risk to send her youngest child across the border of Mexico illegally to give him a chance at a better future.

“My mother always worried about me. She pushed me to get an education,” he said.

Gallardo Parra had an older brother, a U.S. citizen through marriage, living in Iowa. He agreed to take parental rights and responsibilities for his youngest brother and filed the papers to get legal status for Gallardo Parra.

“Just coming to the U.S. as an ordinary person is very difficult. I got denied,” he said. “My mother and brother made a decision I should just come to the U.S. without documents — that it was my best shot.”

He has a harrowing tale of his journey into the U.S., from waiting in the freezing river naked and afraid of being abandoned at one point in a hotel with strangers and no food.

“I was 15 years old; I had no idea what I was getting myself into,” he said.

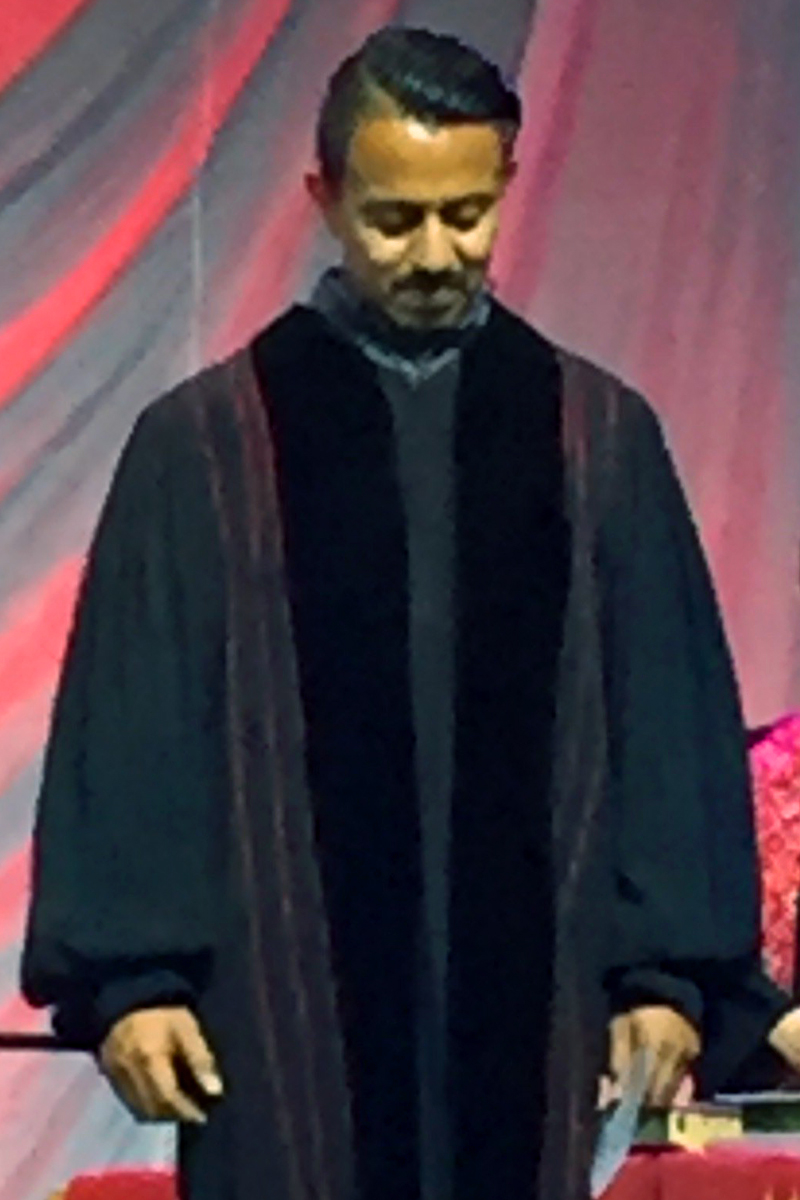

Gallardo Parra, now 33, is a graduate of Saint Paul School of Theology and associate pastor of United Methodist Trinity Community Church in Kansas City. He got a Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals when President Barack Obama signed the executive order in 2012.

DACA allowed certain undocumented young people brought to the U.S. as children to receive a renewable two-year period of deferred action from deportation and eligibility for a work permit.

During the presidential campaign, now-President Donald Trump promised to terminate amnesty programs issued by President Obama and the fate of DACA is unknown at this time.

Nearly 120,000 young people with DACAs, also known as Dreamers, are awaiting a response from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services about the status of their applications for initial or continued inclusion in the DACA program, according to data released in September.

However, the Homeland Security Department is continuing to accept and process requests.

“There is justifiable fear among those who have DACA about their future,” said Rob Rutland-Brown, executive director of National Justice for Our Neighbors, a United Methodist immigration ministry that offers free legal assistance to immigrants.

“Will they lose their work authorization? Will the government use their personal information against them? What happens when their DACA expires? These are all great questions,” Rutland-Brown said.

“JFON sites across the country are receiving an unprecedented amount of calls not just from those with DACA, but from immigrants in general about what their options will be in the Trump Administration,” he said. “Currently JFON sites are not helping people apply for DACA because, based on what Trump has said, it is likely that he will end this executive action and there is a cost and a risk to applying.”

There are two proposals in Congress for how to deal with DACA recipients if Trump repeals the executive order.

A bill introduced by Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., and Minority Whip Richard J. Durbin, D-Ill., would extend protected status for three years while Congress works on a long-term solution.

The second bill by Sen. Jeff Flake, R-Ariz., echoes language in the Graham-Durbin bill but adds a proposal to require Homeland Security Department to detain and place in deportation proceedings any undocumented immigrant arrested or convicted of a serious crime within 90 days of his or her arrest.

There is also a bipartisan proposal in the Senate called the Bridge Act that would also provide temporary relief from deportation and continue work authorization to undocumented youth.

“JFON serves hundreds of aspiring young Americans who have DACA, and we’re inspired by their stories every day. They are school teachers, students, fellow churchgoers, neighbors. This is their home. They should not have to fear losing their jobs or being deported,” Rutland-Brown said.

“Justice for Our Neighbors will continue to remind our communities and our leaders in Washington that those with DACA represent what it means to be American and deserve permanent access to the same opportunities as all Americans,” he said.

Gallardo Parra believes his mother’s prayers got him to this point in his life. He counts it as divine intervention that he got into high school in Waterloo, Iowa, into college at the University of Northern Iowa and to Saint Paul School of Theology in Kansas City.

An internship at Trinity United Methodist Church in Des Moines, Iowa, ignited his call to ministry within The United Methodist Church.

He is a provisional member of the denomination and appointed to the church where he does ministry with Latino and Anglo young people. He was married July 16 to a “beautiful woman named Emily.”

If he is deported, he may be forced to leave the U.S. and go back to Mexico for as much as 10 years. He has petitioned for a waiver from that ban.

“With DACA, I was able to answer my call to ministry. I know a lot of DACA recipients that have been able to develop themselves and they are really afraid now,” he said.

Gallardo Parra is working to make his church a sanctuary church that would shelter anyone threatened with deportation.

Gilbert is a multimedia news reporter for United Methodist News Service. Contact her at (615) 742-5470 or [email protected]

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.