June 13, 2017 | CHIVI, Zimbabwe (UMNS)

Margaret Tagwira feels the heavy burden African women bear for the survival of their families.

As an agricultural researcher at United Methodist Africa University, she has made it her life’s work to ease the load placed squarely on the slender shoulders of women as they struggle daily to feed their families.

Tagwira, a senior laboratory technician, earned a master of public health and graduate diploma in Non-governmental Organization management from Africa University. She was responsible for planning and setting up the first laboratories at the school.

Her compassion for women has made her an evangelist for chaya, a drought-resistant shrub she calls a “woman’s plant” because it is loaded with protein, iron, calcium, potassium and Vitamin A — all essential nutrients, especially for women and babies.

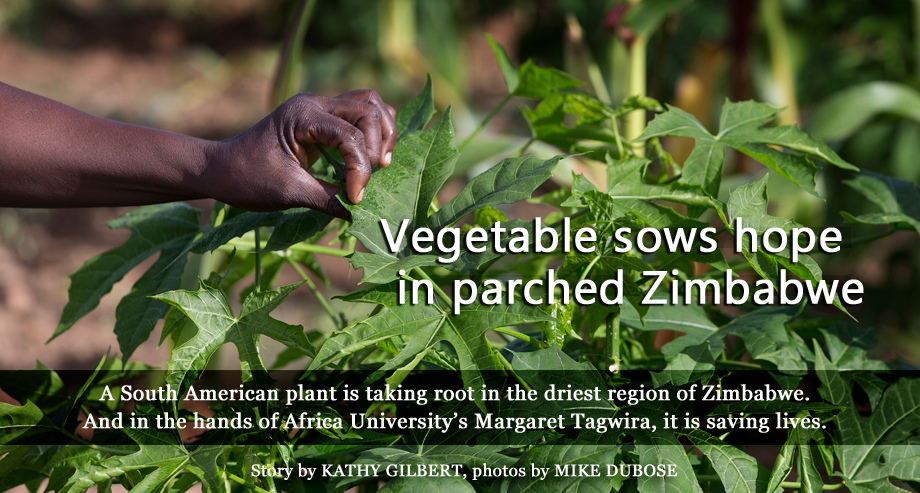

Sarudzai Mkachana (left) and Regina Mavuko tend chaya plants in Chivi, Zimbabwe. The plant contains twice the protein, iron and calcium of spinach and six times Vitamin A of spinach. Photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS.

She has complete faith God is leading her to put chaya on every plate. And, just like Johnny Appleseed left apple trees in his wake, she is leaving a trail of chaya bushes everywhere she goes. She can tick off the virtues of the vegetable in a snap of her fingers.

“Chaya contains twice the protein, iron and calcium of spinach and six times more Vitamin A. Its leaves are available for 10 months of the year. It can thrive in drought-prone areas because it needs little water,” she said.

Women lose a lot of blood in childbirth. And because their focus is on their families, they often miss meals. Women spend hours in a day getting water. Because chaya requires less water than other crops, it means fewer backbreaking walks to and from water sources.

Margaret Tagwira describes the nutritional advantages of chaya amid a field of the fast-growing vegetable. Photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS.

While this rainy season has been a blessing, Zimbabwe suffers crippling droughts. It is estimated that more than 4 million people are in need of food aid.

Chaya in a family’s garden provides the all-important relish to eat with the country’s staple of sadza — a starchy, tasteless dish made from ground maize. Sadza is filling but not particularly nutritious, although no meal is complete without it.

Women pride themselves on offering a delicious relish that turns sadza into a gourmet dish.

Chaya seems an unlikely choice because it doesn’t look like a vegetable.

Margaret Tagwira (second from left) has a joyful reunion with women who are growing the chaya plant in Chivi, Zimbabwe. From left are: Sarudzai Mkachana, Tagwira, Regina Mavuko, Sylivia Shuro Kamurai and Modesta Manzungo. Photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS.

With large, maple-like leaves, chaya is a pretty plant with a compact growth pattern that makes it attractive as a hedge. It will grow to a height of 6 feet and up to 50 percent of its leaves can be harvested without affecting its growth.

It is easy to grow from cuttings; just take a “stick” and plant it in the ground. It does need good watering the first few weeks but is drought-resistant after it is established.

Farmers are ecstatic that chaya is one vegetable that monkeys — notoriously destructive to vegetable gardens — won’t eat.

Africa University Chaya Project

The Chaya project is being funded by John Huie, a member of Tice United Methodist Church in Fort Myers, Florida. He retired from Purdue University as professor and administrator. He has multiple degrees — bachelor, master and Ph.D. — in agriculture economics.

He also has a unique tie to Africa University. His parents were United Methodist missionaries in Zimbabwe and he was born at Old Mutare Mission. The United Methodist Church in Zimbabwe donated 1,542 acres of land in the Nyagambu River Valley across the road from the Old Mutare United Methodist Mission Center to establish Africa University.

His family returned to Zimbabwe but then left after his father died in 1950 following World War II. He became aware of Africa University after hearing the Rev. John Kurewa, founding vice chancellor of Africa University, talk about the United Methodist university at a conference at Purdue University in 1994. Kurewa invited him to visit the school and he met Tagwira there in 1997.

Goats on the other hand, love chaya. That problem is solved with a fence, Tagwira said.

When people hear chaya can’t be eaten raw they often wrinkle up their noses. This is when Tagwira really gets passionate.

“Chaya tastes good!” she will tell anyone. “All it takes is a few minutes of cooking.”

She is developing recipes for a cookbook. Among her recipes are a chewy breakfast bread, stewed chaya with tomatoes and onions, and her personal favorite: chaya pizza with cheese. She also makes chaya tea.

Tagwira has been strategic in introducing the plant, taking it to mission hospitals, orphanages and schools in parts of the country hit hardest by drought.

She brought 100 cuttings to her home village of Chivi in May 2016. When a team from Africa University visited in February 2017, the farmers could show them the thriving, green chaya plants next to wilting and brown maize and grass.

In Chivi, Tagwira put chaya in the hands of someone she knew she could trust — her sister-in-law, Sarudzai Mkachana.

Mkachana is a widow with three children, including a daughter with cerebral palsy. Mkachana teamed with Regina Mavuka and 10 other women farmers, many of them also widows raising orphans.

“Widows make the best investors,” Tagwira said. “They don’t have to ask a husband for permission to plant chaya in their gardens.”

Mkachana emphasizes, “As a Christian, I was proud to do this for Africa University, which is a Christian university.”

In addition to helping her feed her family, chaya has brought new purpose to her life.

“I now have something to do. I go into the fields to see my farmers, go into the villages and tell them about chaya. It makes me proud as a woman to be doing something for other women that will benefit their lives.”

Mkachana and Mavuka live outside the city limits of Chivi in what is called a “growth point.” There are water taps, but the water is only turned on once or twice a month and then for no more than a day and a half. The main source of water is from a river 8 kilometers away. That’s about 5 miles.

“Every time I have been here, I have never seen any water come from these taps,” Tagwira said, turning and twisting the tall silver tap behind Mkachana’s house.

“There are no flushing toilets. The women save all their dishwater and bath water in large barrels for everyday use. When the water is turned on, the women run with buckets and pans to catch the clean water for drinking and cooking.

“One and half days of water is not enough for a month,” Tagwira said.

Chaya farmers roast peanuts and corn for a snack as they gather to discuss the challenges of introducing the new plant, native to South America, in Chivi, Zimbabwe. From left are: Modesta Manzungo, Sarudzai Mkachana, Regina Mavuko and Sylivia Shuro Kamurai. Photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS.

Inside the hut of Sylivia Shuro Kamurai, one of the other farmers recruited by Mkachana, the women roast peanuts and corn and cut down large stalks of sugar cane to offer to their visitors. Traditional offerings for strangers, Tagwira explained, because you don’t know how long your visitor has been traveling or when they last ate.

The women feed a small fire inside the mud hut while talking about how some people are suspicious of chaya.

“There is a certain belief or culture that there is no one who can just die; if they die, someone has killed them,” Tagwira translated. “Even if you have malaria they will go to a traditional healer and ask, ‘Who has killed my relative?’”

Moreblessing Nagombedze cooks chaya greens, grown on campus, during a meeting of the home management club at Chirichoga High School in Masvingo, Zimbabawe. Photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS.

Kamurai talked about the evil spirit “Chikwambo.”

“People believe if you are richer or healthier than your neighbor, you are using an evil spirit called Chikwambo. Once a thing is smeared with the name Chikwambo, the whole village doesn’t want to touch it,” she said.

Kamurai has been eating chaya and said she is feeling much better.

“Many times doctors will tell us our blood is not enough. Now we have chaya to add iron to our blood,” she said.

Emelly Maringire, 14, fetches water at the end of her school day. The job of fetching water falls mostly to women and girls. Photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS.

The administrator and medical staff at Morgenstser Mission Hospital confirm that sentiment; they are all chaya converts.

One of the signs inside the administrator’s office reads, “Morgenstser Hospital is Baby Friendly.” At any moment, they usually have more than 30 “waiting mothers” in their facility. This hospital averages 70 to 80 births a month.

When a pregnant woman is close to her due date or when a midwife, doctor or nurse feels the woman’s pregnancy is in danger, they insist the women stay at the hospital in the “Waiting Mother’s Wards.”

View photos

View all photos from United Methodist News Service's trip to Afirca University on Flickr.

But the hospital cannot afford to feed them and it is up to the woman’s family to provide food. Patients and families are welcome to harvest food from the hospital’s gardens and chaya is prominent in Morgenstser’s gardens.

Each newborn now goes home with a cutting from the shrub.

“It is a huge task for women to get a meal on the table,” said Monica Nzaraycbani, hospital administrator. “It takes a lot of time and is long, hard work. They still have other chores like collecting firewood, cooking. They are exhausted.”

“When a woman is ill, the garden is also ill,” Tagwira added. “I have seen this happen. By the time the women get well, their garden is gone. That is why they delay going to a hospital.”

At Chirichoga High School, the children are not only eating the green-leafy vegetable, they are planting it, cooking it and writing and singing songs about it.

A line of children stand outside the fence of the garden, backs straight, voices clear.

“I am going to tell you about chaya, it can also be called a spinach tree. It is a South American leaf just discovered by Mrs. Margaret Tagwira. Mrs. Margaret bought this chaya to our area and we want to thank her because she brought life to our community,” recited Panashe Chinyakata, 14.

Chaya plants grow outside the waiting mother's shelter at The United Methodist Church's Old Mutare Mission in Mutare, Zimbabwe. The iron in chaya helps replenish that lost in childbirth. Photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS.

John Chirambamurivo, also 14, chimes in on the virtues of chaya.

“I want to tell you about the nutrients found in chaya. There is vitamin A, B and C. Iron and calcium are also available in this plant. It is nice and good because it can make us stay healthy — it is nice,” Chirambamurivo said.

Janet Rushwaya, a teacher at the school, has formed a home education club that includes experimenting with recipes made with chaya.

“After we got the cuttings we saw there were children in need, so we formed a home management club. I teach them how to cook, how to sweep the house, how to make small gardens,” she said.

Chaya seedlings grow behind a rough fence in Chivi, one of Zimbabwe’s driest areas. The plants are prized for their drought resistance. Photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS.

The seven members of the club are all the heads of their households and have younger siblings to feed. That makes chaya a good choice for them, Rushwaya said.

At the end of the school day, two children walk down the red mud road on their way to get clean water. The road is not difficult to travel but the path to the water source is challenging.

Fresh water flows inside a huge rock cave. The children walk bare-footed through an icy stream and climb over slick rocks. They fill their white plastic pail and prepare to carry it home.

Clean water and enough food to eat are a big part of the lessons the children learn.

Tsaurai Chibvongodze works in the garden at Morgenster Mission Hospital in Masvingo, Zimbabwe, where the chaya plant is grown to help supplement patients' diets. Photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS.

Tagwira loves the pioneers who have tried growing and eating chaya.

“When a child is malnourished, giving them chaya can go a long way,” Tagwira said.

Tagwira has researched climate change and has witnessed the hardships it causes.

“I know the burden of food provision falls on the woman and she has to work twice as hard to put food on the table. Chaya will lessen the burden of women having to travel long distances to fetch water for their plants and it will go a long way in restoring the health of women having lost a lot of blood during the birthing process.”

Gilbert is a multimedia report for United Methodist News Service. Contact Gilbert at 615-742-5470 or [email protected]. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.

Charity Munyama prepares chaya recipes in a test kitchen at the Africa University School of Agriculture in Mutare, Zimbabwe. Photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS.

Emelly Maringire, 14, (left) and Malvin Musengwa, 13, walk to fetch water at the end of their school day at Chirichoga High School. Photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS.

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.