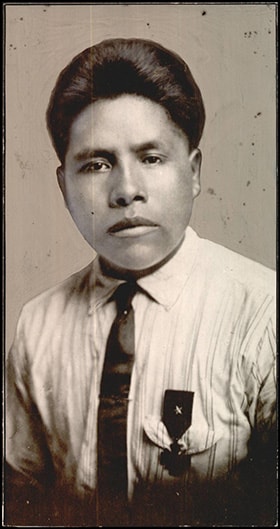

Private Joseph Oklahombi, a member of the Choctaw Nation, is one of the most decorated war heroes from Oklahoma. However, most of his contributions were unknown until after his death.

Oklahombi, from Wright City, Oklahoma, served as a code talker in World War I in the 141st Infantry. This special, highly important assignment involved using his native language to send secret military messages.

“When he came home from war, they told him not to talk about how he served as a code talker in case they needed to use the language again,” said Lee Watkins, a descendent of Oklahombi and member of Chihowa Okla United Methodist Church in Durant, Oklahoma. “For a long time, no one knew what he had done.”

Oklahombi died in 1960 and is buried in the cemetery at Yasho United Methodist Church in Broken Bow, Oklahoma.

Joseph Oklahombi served as a Choctaw code talker during World War I. Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

The Republic of France awarded Oklahombi the Croix de Guerre medal. The French citation recounts how Oklahombi and 23 men were cut off from the rest of the company. Oklahombi ran over 200 meters through a barbed-wire maze and jumped into a machine-gun pit. He turned the captured machine gun against the German enemies and held out for four days without food or water and “despite a constant barrage of large projectiles and gas shells.”

His actions contributed to the capture of 171 prisoners. The citation also stated that he crossed the “no man’s land” territory several times to collect information on the enemy and rescue wounded comrades.

The U.S. Army awarded Oklahombi with the Silver Star with Victory Ribbon for his bravery. No minority soldier at the time had ever received a Medal of Honor. American Indians were not given U.S. citizenship until 1924 and could not vote in some states until 1957.

Many have attempted and are still attempting to get Oklahombi’s Silver Star upgraded to a Medal of Honor.

“He didn’t enlist to be a hero; he did it because he loved his country,” Watkins said.

Oklahombi is one of the many Native Americans who have honorably served their country.

According to the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, Native Americans have participated in each of America’s major military encounters since the Revolutionary War.

The museum website notes that Native Americans have served in the armed forces at one of the highest rates per capita of all population groups, with approximately 31,000 American Indian and Alaska Native men and women currently serving around the world and 133,000 Native American veterans alive today.

The Choctaw Nation Congressional Gold Medal commemorates the work of Choctaw code talkers. U.S. Mint, public domain photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Among the latter is Kiowa tribal member Geneva (Sahmaunt) Foote, who enlisted in the United States Navy on Nov. 7, 1955, at age 18. It was a plan made with her best friend when they were still in high school.

“We saw recruiting photos of women in the military and we admired them,” Foote said.

She was sent to do basic training in Baltimore, where she was issued a uniform that included skirts and stockings, but no pants.

“It was so cold, and we had to march throughout the day,” she recalled.

After completing basic training, Foote decided to study to become an air traffic controller and was later assigned to the Naval Support Facility Anacostia in Washington, D.C.

“Overall, the Navy was a good experience for me,” said Foote. “It has always stuck with me about being disciplined, being on time and doing the best job that you can. I think the military helped in that way.”

After serving four years, Foote was discharged. She pursued a teaching degree at Cameron University in Lawton, Oklahoma, using assistance from the GI Bill. After she married her husband, Bill Foote, he became a United Methodist minister. She retired from teaching to be active as a pastor’s wife.

“We were in the church work for 25 years,” she said.

Even though Foote served in the Navy and was among a small number of Native women in the military in the ’50s, she said she doesn’t promote herself as a veteran.

“It humbles me, because I was never in any harm or danger like many soldiers. They deserve the recognition,” she said.

Geneva Foote in her naval uniform, 1955. Photo courtesy of Carrie Sahmaunt.

The Kiowa Black Leggings Warrior Society Auxiliary honored Foote for her military service. The society, which is more than 300 years old, honors Kiowa male veterans. Women related to society members comprise the auxiliary. They do a processional prior to the Warriors’ entrance during the group’s annual ceremony and Foote has led the march several times.

Bill Durant, another veteran, said he was a pastor’s kid who needed a bit of discipline. His father, Forbis P. Durant, served in the Oklahoma Indian Missionary Conference for 47 years.

The younger Durant enlisted in the United States Marine Corp. in 1971, during the Vietnam War, with his best friend from Atoka High School.

“After graduation, we went to boot camp,” Durant said. “He went into the air wing and I went into communications.”

Durant was a field radio operator, also known as a “radio humper.”

He served for three years, 11 months, 29 days, eight hours and 47 minutes.

“You just remember every minute,” he joked.

He credits his Chickasaw and Choctaw heritage for the inspiration to serve in the military. He said that even though Native Americans suffered great atrocities, such as broken treaties and forced removal from their lands, they still never backed down from a call to fight.

“From the French war to now, Native Americans said, ‘We are here, and we are going to protect our community, our people, our name, our tribe.’ They never backed down,” he said.

Durant also was inspired by his older brother, Forbis P. Durant Jr., who was killed in Vietnam. He said that even though his own experience in the war was difficult, his faith was strengthened.

“There is a greater power that brings you through the most difficult, worst things that you can see or ever experience in your life.”

He recalled seeing chaplains and people of the cloth leaning over soldiers and talking with them and letting them know that they were loved before they left this earth.

“Everyone has the road they have to walk down,” he said, referencing the poem “The Road Not Taken” by Robert Frost. “There’s two roads in life. Keep your head right with God and he will never leave you.”

Today, Durant is back in his hometown of Atoka, Oklahoma, and enjoys early morning coffee alongside his best friend who he enlisted with so many years ago.

Ginny Underwood is a communication consultant with ties to the Oklahoma Indian Missionary Conference. She is a member of the Comanche Nation of Oklahoma.

News media contact: Vicki Brown at 615-742-5470 or [email protected]. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.