The poor have no one staging mass protests on their behalf, but religious leaders are speaking out about how proposed changes to the U.S. budget for 2011 and 2012 could affect them.

"The message is consistent year in and year out: We want to make sure we're protecting those living in poverty or on the economic margins both in the U.S and around the world," explained John Hill, an executive with the United Methodist Board of Church and Society.

In a March 1 letter to Congress, 16 religious leaders — including United Methodist Bishop Larry Goodpaster, president of the Council of Bishops, and the Rev. John McCullough, the United Methodist executive director of Church World Service — expressed their full commitment to ministry with the poor.

"None of us can prosper and be secure while some of us live in misery and desperation," the letter said. "In an interdependent world, the security and prosperity of any nation is inseparable from that of even the most vulnerable both within and beyond their borders."

Last month, President Barack Obama released his budget proposal for 2012, and the U.S. House of Representatives passed a $61 billion budget-cut package for the rest of the 2011 fiscal year, which ends Sept. 30. The U.S. Senate has yet to agree on the cuts, so Obama signed a budget extension bill March 2 that will keep federal agencies open through March 18 and enact $4 billion in new spending cuts.

Politicians on both sides of the aisle are proposing draconian cuts that will greatly compromise "our capacity as a nation to respond to situations of need," McCullough said. "The budget reduction essentially reduces what we would call the safety net for poor people and for vulnerable communities here in the United States."

Faith leaders understand the concerns over the nation's financial deficits. However, drastically reducing discretionary programs for the poor that constitute an extremely small part of the budget is not a solution to the economic crisis, they pointed out in the letter to Congress.

"These cuts will devastate those living in poverty, at home and around the world, cost jobs, and in the long run, will harm, not help, our fiscal situation," the letter said. "While 'shared sacrifice' can be an appropriate banner, those who would be devastated by these cuts have nothing left to sacrifice."

The sacrifice is global, not just local, said Thomas Kemper, top executive of the United Methodist Board of Global Ministries. And while only a fraction — 0.5 percent — of the budget relates to international aid, "for the people who are affected by these cuts, it makes a lot of difference."

Ethical implications

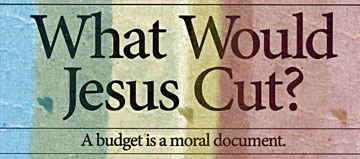

Budget decisions have ethical as well as financial implications, say Christian leaders organized by Jim Wallis and Sojourners, a faith-based social justice organization. Those leaders took out a full-page ad in the Feb. 28 edition of Politico, a website devoted to politics.

Titled "What would Jesus Cut?" the ad declared, "A budget is a moral document." It called upon legislators to defend international aid for pandemic diseases, critical child-health and family-nutrition programs, "proven" work and income supports for poverty-level families and educational support, particularly in low-income communities.

Winsley Polo, 2, lies in her crib outdoors beneath a tarp at Grace Children's Hospital in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, following the January 2010 earthquake. Church leaders have been advocating for ministries with the poor amid calls to cut federal spending. A UMNS file photo by Mike DuBose.

"Our faith tells us that the moral test of a society is how it treats the poor," the ad said. "As a country, we face difficult choices, but whether or not we defend vulnerable people should not be one of them."

Engaging in ministry with the poor is a mission priority for The United Methodist Church, and its 13 agencies and commissions have adopted "guiding principles and foundations" for that work.

"It's fundamental to our faith that we care for the poor and vulnerable," said the Rev. Larry Hollon, top executive of United Methodist Communications. He noted that, in the Wesleyan tradition, holiness does not exist without social holiness. "We are a faith community who believe faith should not only promote our personal growth; it should also equip and mobilize us for mission and service to the world."

The understanding of that ministry goes beyond charity, Kemper said. "It's not only about giving money; it's not only about doing a soup kitchen; it's about personally being involved and being with the poor," he explained.

Advocacy actions over federal budget matters since January have included a call by church leaders to Obama to renew his campaign pledge to "cut poverty in half" in the next 10 years and a Valentine's Day lobbying effort to "show love" and make the poor a priority. After the House bill passed, National Council of Churches leaders drafted the March 1 letter "that reflected our deep concern that these cuts are particularly impacting the ministries that we do, both in the U.S. and around the world, that are anti-poverty," Hill said.

Alternative solutions exist, he argued. At times of fiscal crisis in the 1990s, Hill noted, Congress was able to make reductions while still protecting those in poverty. "As a result, even though there were very large cuts, poverty rates were down," he said. "We're basically asking them to do that again."

International aid cuts

The House bill cuts in the 2011 budget also would greatly affect international assistance, according to the Washington Post, slashing international food-aid programs by up to 50 percent and State Department funding for refugees by more than 40 percent.

The International Disaster Assistance Fund would be reduced by 67 percent, even though, McCullough pointed out, it is obvious from the outpouring by Americans for victims of disaster like the Asian tsunami and Haiti earthquake that "people expect the United States is going to be in a position to respond to these types of disasters."

Sojourners, a faith-based social justice organization, took out a full-page ad in the Feb. 28 issue of Politico, a publication devoted to politics. A web-only photo courtesy of Sojourners.

Humanitarian agencies like Church World Service already are aware, he added, that when resources for aid and development work are severely curtailed "the potential for (human) survival diminishes dramatically."

It also makes no sense to cut aid that helps avoid military conflicts and fights terrorism, said Kemper, using as an example the new nation of South Sudan that is emerging after years of civil war. "If you take away funding and aid from these countries, they get more fragile," he explained.

Because of the denomination's pledge to help eradicate malaria, United Methodist leaders are particularly concerned about the House bill's decrease in the U.S. contribution to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Malaria and Tuberculosis by 40 percent. Kemper called it "a blow" to church members trying so hard to raise $75 million themselves through the "Imagine No Malaria" initiative.

Some of the "unacceptable" consequences of that budget reduction, said Hollon, whose agency promotes Imagine No Malaria, were pointed out by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton when she spoke to the House Foreign Affairs Committee. Those consequences include the denial of treatment and prevention measures for malaria to 5 million children and family members; denial of treatment for tropical diseases to some 16 million people and a loss of millions of available polio and measles vaccines.

"It means children will die, more people will get sick, and preventable diseases will not be prevented," Hollon said.

*Bloom is a United Methodist News Service multimedia reporter based in New York. Follow her at http://twitter.com/umcscribe.

News media contact: Linda Bloom, New York, (646) 369-3759 or [email protected].

Related Articles

Democrats offer $6.5 billion in cuts

House budget bill's deep cuts in humanitarian aid criticized

Budgets: Can't cut moral responsibilities to save lives, say faith leaders

Love and justice are primary in guidelines for ministry with the poor

NCC communion leaders remind Obama of his promise to cut poverty in half

Resources

President's proposed 2012 budget

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.